on October 8, 2019

Genres: Non-Fiction, Memoir

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

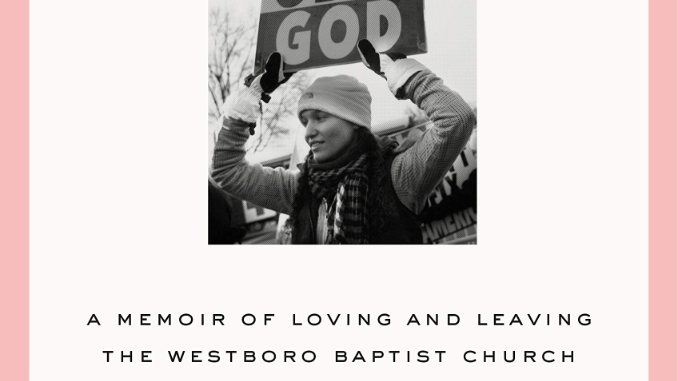

At the age of five, Megan Phelps-Roper began protesting homosexuality and other alleged vices alongside fellow members of the Westboro Baptist Church in Topeka, Kansas. Founded by her grandfather and consisting almost entirely of her extended family, the tiny group would gain worldwide notoriety for its pickets at military funerals and celebrations of death and tragedy. As Phelps-Roper grew up, she saw that church members were close companions and accomplished debaters, applying the logic of predestination and the language of the King James Bible to everyday life with aplomb—which, as the church’s Twitter spokeswoman, she learned to do with great skill.

Soon, however, dialogue on Twitter caused her to begin doubting the church’s leaders and message: If humans were sinful and fallible, how could the church itself be so confident about its beliefs? As she digitally jousted with critics, she started to wonder if sometimes they had a point—and then she began exchanging messages with a man who would help change her life.

A gripping memoir of escaping extremism and falling in love, Unfollow relates Phelps-Roper’s moral awakening, her departure from the church, and how she exchanged the absolutes she grew up with for new forms of warmth and community. Rich with suspense and thoughtful reflection, Phelps-Roper’s life story exposes the dangers of black-and-white thinking and the need for true humility in a time of angry polarization.

Westboro. I probably don’t even have to finish the church’s name for the images of protestors carrying signs with slurs to march through your mind’s eye. For thirty years, Westboro Baptist Church, under the leadership of Fred Phelps, came to define fundamentalist, hate-filled Christianity. Even to most conservatives—even those who believed that homosexuality was sinful—the methods and vitriol of Westboro have long stood out as sensationalist and against the message of Christ. But because of its sensationalism and its marketing prowess, this small group of forty or so people have wielded an influence that has shaped pop culture views of American Christianity.

As the years have gone on, and especially as the second-generation of Phelpses have become adults, several prominent members have either left or been excommunicated. None perhaps more prominent than Megan Phelps-Roper. Megan was the online extension of the WBC in the early days of social media. She writes of being thirteen and defending their views in anonymous chatrooms and message boards and comments on news articles. That eventually turned to Twitter—which would both introduce the small “church” to the larger world, but also introduce an introverted, reclusive girl into that big, big world.

In early 2013, Phelps-Roper decided to leave the Westboro community. She had begun to question the family’s values and methods, and the elders would bear no difference of opinion. In the six years since, Megan has become an activist and expert on communication across ideological divides. Unfollow is the natural extension of that: an unfiltered, honest, and even loving memoir of growing up in America’s most hated family.

There is a complexity to Phelps-Roper’s story that is utterly compelling. She doesn’t demonize her family or paint her past in a grim light. In fact, the scariest thing about the early chapters is how eerily normal and loving and intelligent the Phelps family can be. This isn’t Jim Jones or David Koresh or some other charismatic cult leader, where you know the powder keg is going to explode soon. Westboro is a slow burn of fundamentalism, a cornucopia of contradictions, and a thoughtful and deliberate extremism. They aren’t crazy. They’re cunning. They aren’t insane. They’re tactical.

What you saw in a lot of conservative households and conservative churches in the 1970s-1990s played out in the extreme in the Phelps household. And they were great at marketing it. And once they had success through hate, they were determined to hold on to that hate to spread their message. Phelps-Roper grew up in the middle of that. She paints an honest portrait of a little girl who was a genuine believer, who had been thoroughly indoctrinated to believe that any opposition was persecution, and then whose early adulthood saw those beliefs—and the church structure itself—begin to crack.

Unfollow is not told exactly linearly, instead using overlapping chapters based on different themes. This technique allows Phelps-Roper to intensely hone in on a certain belief within Westboro or struggle in her own life and consider it with complexity and depth. The middle chapters—The Tongue is a Fire, The Lust of the Flesh, and The Appearance of Evil—not only serve to flesh out Westboro’s theology but foreshadow the underpinnings of why she later leaves the church. Megan’s storytelling is simply superb, managing to portray in depth an organization that almost deliberately presents itself as a caricature.

Two threads that impacted me the most was seeing how much good simple and honest conversations can do. Ultimately, Phelps-Roper left the church because of challenging conversation she had with people online willing to respectfully engage her positions. It is so easy to respond to fire with fire, to escalate a disagreement, to troll the troll—and this was Westboro’s positions. But a few individuals (and I shan’t name them here, just read the book) willing to form a genuine relationship and befriend a member of America’s Most Hated Family is what eventually led to her recanting her life of hate.

Second, people are complex. Fred Phelps was a lawyer in the South who openly fought against Jim Crow laws and the KKK. He had been honored by the NAACP. There’s a definite cognitive dissonance between this progressiveness and his later life. Even in his personal life, he is both presented as a loving patriarch and a fearsome abuser. In many ways, you can see how Phelps’s hatred in one of his life soon grew to consume him.

Unfollow is a magnificent work of memoir. It’s intelligent and thoughtful. It doesn’t seek to fit a narrative, but presents Westboro in a startling complexity that belies the church’s own public presentation of itself. It’s an introspective and challenging story that you just have to take your time and soak in.

My prayer is that fifty years from now, Unfollow is all that remains of Westboro’s legacy. It’s a reminder that there is always hope against hate and that the battle is best waged with words and compassion.