Podcast (beyond-the-page): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Who Will Be a Witness? is one of those books I’ll come back to time and time again. Deeply theological yet deeply practical, Drew Hart offers an outright manifesto of the church’s need to be involved in the pursuit of justice. He deftly digs into American history and shows our roots of nationalism and white supremacy—not for the purposes of shame but for the purposes of removal. It is a kind, firm, bold stance that plainly tells us our problems while offering Scriptural solutions.

The only thing better than reading this book was this hour-long conversation I had with Drew about it. Go order Who Will Be A Witness and while you wait on to arrive, enjoy this conversation with Drew and myself.

The Conversation | Drew Hart

This excerpt has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity. You can listen to the full interview by clicking the play button above or subscribing at Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Josh Olds: What do you see that we need to change in the way in which we perform our activism? Especially here in 2020, that’s been such a relevant question of how do we protest? How do we make sure that our voices are heard?

Drew Hart: Yeah, I mean, and it really in some ways, it depends on where we’re coming from, right? Because I think different communities are approaching it differently. Some of us are framing and entering into the conversation in terms of political engagement and are deeply captive to our society and the partisan fights that are going on. So for some of us, we start with the political platform of a particular political party. And then we just buy into that wholesale and then go fighting. Literally, there are some wealthy elite people who package up these platforms for us, and give it to us and then we say it represents our voice. And it seems to be backwards.

But I think if we take Jesus’s example, we’re living in solidarity with those who are vulnerable, we’re in proximity to them, and we’re experiencing and witnessing and sharing in their suffering, right? And I think that that’s the starting point for a grassroots work first, not starting with the elite first, but starting with the grassroots, and then bringing those concerns. And in that sense, like, Jesus has this confrontation with the establishment, and especially in the Gospel of Luke, it’s particularly profound and powerful because of the confrontation that he has with the establishment, willing to, in essence, shut it down on and accept the consequences of faithfulness for bearing witness in the public square…And I think that that is a really beautiful example that doesn’t leave us captive to those who are in power, but instead, it does the opposite.

One of the things in both Mark and Luke, Jesus actually says, you know, they devour—he’s talking about the religious leaders and their long prayers and all that—they can devour widows’ homes, right? He comes into the temple, and the names and identify the ways that they have gone against God’s vocation for all of us, right? And I think that that is a healthier way to go about social change work.

We’ve got to be willing to accept the consequences of following Jesus faithfully in our own society in such ways that include taking upon, accepting the risks for standing against evil and injustice…Jesus is actually very strategic about what he’s doing. He embodying the good news, literally, through his life in such a way that that is evoking something in those who are watching him. They understand exactly what this means. And it’s awakening people to the possibility and reality of God’s reign on Earth, coming here and being realized, in their own communities, in that they ought to then also strive after that.

We’ve watered down the meaning of “Take up your cross”…in the first century, it meant actually accepting the consequences of clashing with the Empire, which could mean anything up to and including death, right? Like, that’s what it actually meant. And, and so we’ve watered it down to our domesticated, comfortable lifestyles, and we’ve got to recover more of the non-violent revolutionary witness that we see in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Josh Olds: I want to keep on this thread of non-violence because I’ve had this conversation so many times since the murder of George Floyd, and the sometimes violent reactions that there have been—provoked or not. For many on the conservative, white evangelical side, there’s always this well, “You know, we have to condemn the rioting” all the way up to “The increased level of police violence is justified because of the behavior or alleged behavior of the way in which these protests are going about.” I personally cannot condone any sort of violence. I myself, am a practitioner of non-violence and peacekeeping. But I understand, like, I empathize so thoroughly with this, you know?

I think we can make the argument that violent revolutions are not as successful as non-violent revolutions. There are studies show this. Erica Chenoweth, I can remember her name, but not the book that she wrote off the top of my head [ed note: Why Civil Resistance Works], studied non-violent and violent revolutions and found that non-violent revolutions had more staying power, because how you do a revolution, then becomes the kind of principles that become in power. So you end up replacing violence with violence.

In light of that, how do we find the line of understanding and empathizing while also taking a stand and saying that we are committed to non-violence?

Drew Hart: Yeah, and I think, you know, the challenge is, is that we’ve got to have a really a healthier, robust analysis of violence. That’s the starting point, right?

And I think that if we did it probably would shift our conversations quite a bit because many of the people who condemn people who are rioting, or maybe burning down a building are actually they themselves sustained by systems of violence, perpetuate systems of violence, and push ideologies that are endorsing “law and order” violence. Even our language needs to shift altogether if we’re truly going to be committed to peacemaking and non-violence.

The example I give is, imagine we walk into a room, and we see an adult beating down on a toddler. They’re just beating down on a toddler, the toddler’s on their back and they’re just taking a beating. And we see the toddler hit back. They hit the adult once. Now imagine how ludicrous it would be if we went intervened and said, “How wrong of you, Child, for hitting back?”

You know that’s not constructive. That’s not going to lead to this adult stopping hitting. You know, that would be silly. That would be in fact, not just silly, it would be wrong, right? Because our focus on that “violence,” if we would even call it that, is so miniscule compared to the bigger violence that’s happening in that moment. And I would describe that similarly, in terms of our own moment, in terms of thinking about Black people’s frustration, like, the US Government literally has been beating down on Black people for centuries. It’s so strange all of a sudden, that people want to walk into the room and see a Target burn down and they want to condemn that, but have nothing to say about the centuries of violence that continues today. Violence in forms of mass incarceration and police brutality and underfunding schools and ghettos, and who has access to resources—all kinds of stuff that continues to bring harm and oppression to Black communities, poor Black communities, in particular.

We cannot only focus on how people respond and deal with their oppression, and not deal with the systems of violence that are cycling and destroying people’s lives. So that would be my starting point. How do we even name and identify the violence in our world?

But then I am like, I’m a full committed follower of Jesus. And I deeply believe that he invites us to reimagine how change is actually going to come and happen in this world. So when Paul uses that phrase, “the things that make for peace” (Rom. 14:19), he suggests that there are things that actually promote Shalom, the flourishing of all people to the well-being of all that we ought to be in pursuit of. And like you said, social science actually proves the fact that non-violent movements actually have been more successful and more efficient in bringing change.

I don’t necessarily think that destroying property is productive. I don’t think it actually does what we hope it does. In fact, I think sometimes it turns people against really important justice movements. But when we begin to elevate property as more valuable than people, something’s distorted about our value system in and of itself. And I think it’s taken the temperature of our society in the distorted ways that we disvalue, especially Black people’s lives, in our society and overvalue property in such a way that it dismisses and denies that Black Lives actually do matter.

The Book | Who Will Be a Witness?

Churches have begun awakening to social and political injustices, often carried out in the name of Christianity. But once awakened, how will we respond?

Who Will Be a Witness offers a vision for communities of faith to organize for deliverance and justice in their neighborhoods, states, and nation as an essential part of living out the call of Jesus.

Author Drew G. I. Hart provides incisive insights into Scripture and history, along with illuminating personal stories, to help us identify how the witness of the church has become mangled by Christendom, white supremacy, and religious nationalism. Hart provides a wide range of options for congregations seeking to give witness to Jesus’ ethic of love for and solidarity with the vulnerable.

At a time when many feel disillusioned and distressed, Hart calls the church to action, offering a way forward that is deeply rooted in the life and witness of Jesus. Dr. Hart’s testimony is powerful, personal, and profound, serving as a compass that points the church to the future and offers us a path toward meaningful social change and a more faithful witness to the way of Jesus.

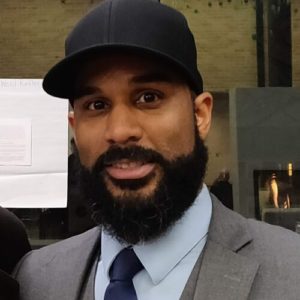

The Author | Drew G.I. Hart

Drew G. I. Hart is an author, activist, and professor in theology in the Bible and Religion department at Messiah University with ten years of pastoral experience. Hart majored in Biblical Studies at Messiah College as an undergrad, he attained his MDiv with an urban concentration from Biblical Theological Seminary, and he received his PhD in theology and ethics from Lutheran Theological Seminary-Philadelphia.

Drew G. I. Hart is an author, activist, and professor in theology in the Bible and Religion department at Messiah University with ten years of pastoral experience. Hart majored in Biblical Studies at Messiah College as an undergrad, he attained his MDiv with an urban concentration from Biblical Theological Seminary, and he received his PhD in theology and ethics from Lutheran Theological Seminary-Philadelphia.