Also by this author: The Promise, The Drummer Boy, Sinner, Green, The Dream Traveler's Quest, Into the Book of Light, The Curse of Shadownman, The Garden and the Serpent, The Final Judgment, Millie Maven and the Bronze Medallion, Nine, Millie Maven and the Golden Vial, Millie Maven and the White Sword, Millie Maven, And They Found Dragons, The Light of the One, The Dragon Rider Who Saved the World, The Unknown Path

Series: The World Fixers #1

Published by Scripturo on October 1, 2025

Genres: Children's, Fiction, Fantasy

Buy on Amazon

In a land called Cora, live two teenagers who unwittingly hold the future of the world in their hands. Their names are Andrew and Heidi. They are bitter enemies.

When Andrew’s father goes missing after discovering an ancient book of secrets which contains a map that promises peace if followed, Andrew becomes desperate to find him. But following the map is a dangerous journey that begins in the enemy’s capitol—only a fool would attempt such a dangerous undertaking.

So begins a whimsical yet very serious morality tale full of wild adventure and critical life lessons that mirror the challenges we all face today in a deeply divided world.

Ted and Rachelle Dekker have each forged wildly successful careers in traditionally-published Christian fiction. In 2019, the duo teamed up for The Girl Behind the Red Rope, which made them the first and so far only father-daughter duo to share a Christy Award. That team-up soon spilled over into the middle-grade realm with the tween fantasy series Millie Maven, And They Found Dragons, and The Dragon Rider. Now, at the end of 2025, they’re adding to that list a brand-new trilogy called The World Fixers.

Unfortunately, I’ve found the Dekker team-ups to be a series of recycled storylines and diminishing returns. Don’t be ruled by fear is a powerful message, but it’s been the only message since The Girl Behind the Red Rope. Throw in some stock fantasy tropes, some Blank Slate Protagonists, some sort of quest, and a dragon or two, shake it all up, and see what comes out. It’s more of the same, but not presented with any more (literary or thematic) depth than the previous offerings. In fact, I’d say the opposite is true. With each series, the story takes a larger and larger backseat to hammering home the theme. But, sans story, the theme is left without a lot of weight.

The World Fixers begins with Book 1: The Blue Boy and the Red Princess. The cover art for the book shows us a fractured globe—half tinged red, half tinged blue—with said boy and princess facing each other at the fracture. In this world are two peoples—the Redbloods and the Bluebloods—and they hate each other. There’s no great substantive reason why. They eat corn instead of rice, raise goats instead of sheep, play the flute instead of the harp, etc. It’s played like a simplistic caricature for a young audience, but there’s no weight behind any of it.

Our main character is a young boy named Andrew whose father is the king’s Balancer. The Balancer is the person whose job is to “restrain the pride and rage of the king.” (We are never shown what this means or what it entails.) One night, Andrew sees a talking bird give his father a map. Unfortunately, the Balancer is kidnapped soon after and Andrew is forced into a journey to find his father. He takes off for the Red city, but not before learning that long ago, the founders of each city were offered a relic by a sage—one a book with a map, the other a key that would unlock the secrets of the map.

Andrew goes off in search of his father, who he believes has been kidnapped by the Red City because of the map. He is immediately captured, of course. And finds out that Red City doesn’t have his dad. But he does meet a princess named Heidi. And that, excepting one final twist I’ll leave a surprise, is the synopsis of The Blue Boy and the Red Princess.

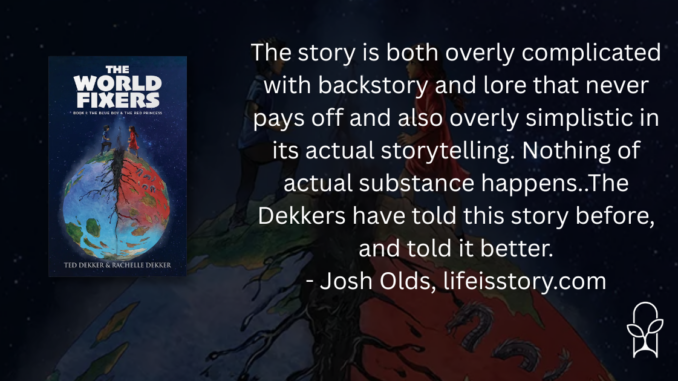

It’s not good. The story is both overly complicated with backstory and lore that never pays off and also overly simplistic in its actual storytelling. Nothing of actual substance happens. The Dekkers also decided on extensively using the rhetorical device of an interjecting narrator (where, dear reader, the storyteller interjects their own thoughts—like a person reading a book aloud and then looking up to offer commentary. This isn’t a bad device, but [like this parenthetical] the series uses it about once every other page, disrupting the narrative flow.)

Ted Dekker made a name writing allegorical fiction that was both simplistic and deep. Ted saw story as a more powerful alternative to didactic non-fiction. I understand that themes and symbolism have to be a littler simpler for an audience of children—but that doesn’t mean they need to be childish and spelled-out within the text. And even then, there has to be substance in the story.

The back cover designates this series as a “whimsical yet very serious morality tale full of wild adventure and critical life lessons that mirror the challenges we all face today in a deeply divided world.” Yet while the book pays lip service to those divisions, we never actually see anyone working out those differences and are never given reasons for those differences. The theme of “fear of the Other” is a strong and powerful one—very relevant to our times. The solution to that problem—to truly know the Other—is also very powerful. But it plays out very weakly in the books.

Combine all of that with grammatical and punctuation errors—at one point the Dekkers write “the damn broke” instead of the “the dam broke” referring to Andrew sharing his pent-up emotions with his grandmother. A silly typo, but you know in books marketed for young children, the damn “damn” is going to make someone angry. In short, this book (and the series) needed an outside perspective—a copy editor, a structural editor, any sort of outside voices to help the Dekkers take the world in their heads and make sure it translated to the page. I had seen this problem with other Dekker middle-grade books, but not with ones co-authored with Rachelle. I know the Dekkers can do better. I have twenty-five years of books on my shelf to prove it.