Also by this author: Niños: Poems for the Lost Children of Chile

Published by Eerdmans Books for Young Readers on October 27, 2020

Genres: Children's

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

On May 27, 1937, over four hundred children sailed for Morelia, Mexico, fleeing the violence of the Spanish Civil War. Home was no longer safe, and Mexico was welcoming refugees by the thousands. Each child packed a suitcase and boarded the Mexique, expecting to return home in a few months. This was just a short trip, an extra-long summer vacation, they thought. But the war did not end in a few months, and the children stayed, waiting and wondering, in Mexico. When the war finally ended, a dictator—the Fascist Francisco Franco—ruled Spain. Home was even more dangerous than before.

This moving book invites readers onto the Mexique with the “children of Morelia,” many of whom never returned to Spain during Franco’s almost forty-year regime. Poignant and poetically told, Mexique opens important conversations about hope, resilience, and the lives of displaced people in the past and today.

I’ve started to write this paragraph three times and each time end up erasing it out of fear that I’ve not captured the essence of this book. Mexique is a children’s book, but it’s more than that. Usually, children’s books are brightly-colored light-hearted affairs with catchy rhymes and fun illustrations. They are not usually poetic descriptions of the plight of early twentieth century child refugees.

Until I read this book, I was unaware of the story of the Mexique, a ship that fled the Spanish Civil War with over four hundred children in tow. They were only supposed to stay in Morelia, Mexico for a few months. Until the war was over. Until things settled down. But when things settled down, a dictator was in power. Francisco Franco had taken over. It was more dangerous than ever. They could not return. And the Children of Morelia became forever exiled from their homes.

Mexique is not a happy story. Written by Maria Jose Ferrada and translated by Elisa Amado, its focus is the journey from Spain to Mexico. Ferrada gives a voice to the children: I can’t really remember where it is we are going, but it is far. She writes from their perspective of the war they are fleeing: War is a very loud noise. War is a huge hand that shakes you and throws you onto a ship.

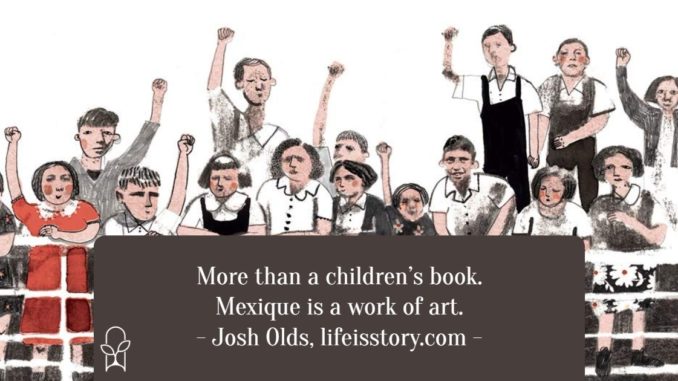

Ana Penyas provides illustrations that are as muted, cacophonic, and jarring as the story. The illustrated children are given faces more realistic than their bodies, forcing readers to acknowledge that these children aren’t faceless refugees, but children with expressions, texture, and personality. Black, white, gray, and dashes of drab red are her only palette, a dreary rainbow that accurately captures the hopefulness and despair in the book.

Mexique is important because it tells an unknown story. It’s important because it points us toward the unknown stories of our times. It humanizes the refugee crisis of today, highlighting the separation of families, the loss of identity, the loss of culture. The book ends: We tell the story of one ship, knowing that there is no registry of all those who cross the sea, every day, seeking that basic human right: a life without fear.

It is about 1937.

It is about 2020.

It is about the refugee crisis then.

About the refugee crisis now.

It is the beginning of many conversations about the lives of displaced people and what we can do as individuals, churches, communities, and nations. Mexique is more than a children’s book. It’s a work of art.