I’ve been reviewing books professionally for over ten years. Give me a non-fiction book and I can analyze it, deconstruct it, and put it back together in five hundred words. Throw me some fiction and I’ll pick at its themes, structure, and tone and make you want to buy it in five hundreds words or less without giving anything away.

But then I had kids.

And I had to stare down the Children’s Book Section.

Specifically, I had to stare down the Children’s Bible Stories Section.

Every Christian publisher pretty much every year publishes a new take on the Christmas and Easter stories. Every Christian publisher pretty much every year publishes some new anthology collection of some sort of Bible stories. There are literally thousands. How are we to choose?

It was overwhelming. As a pastor and professional reviewer, I decided I had to make myself some guidelines. What makes a children’s Bible story stand out? Here are four guidelines:

Accurate

Is the story biblically accurate? Occasionally, children’s Bible stories get reduced or fleshed out to the point of inaccuracy. And yet, again and again, I see Bible stories—particularly retellings of Old Testament tales—that leave us with very inaccurate assumptions about characters like Gideon, Samson, or Jonah. The nuance and complexity of these historical characters and their narratives get reduced to simplistic morality tales.

Other times, children’s Bible stories will add to the biblical narrative in a way that harms its accuracy or adds an applicational point that might be accurate but not a correct or primary application to that particular Scripture.

This doesn’t mean the story has to only be the Bible put into simpler language, unless it is marketed as a Bible paraphrase or translation. Many Children’s Bible stories purposefully go outside the Biblical text without going against the Biblical text.

For example, it is appropriate to give us insight into what a character may have been thinking or doing when Scripture is silent—so long as it fits the story. This does run the risk of an author inserting their own biases or feelings into the character, but when done well it makes obvious to children what they would not otherwise grasp. In this type of story, Bible storybooks become sermons that interpret and exposit the Biblical text.

That’s the best way to take most Bible storybooks. It’s not Scripture. It’s an interpretation of Scripture. It’s a children’s sermon meant to exposit upon the selected text, to give background information based on history, culture, and context. Just a pastor (hopefully) makes the Biblical text come alive, a good Bible storybook should do the same for children.

In The One O’Clock Miracle, Alison Mitchell tells of the Roman officer in Capernaum who travels to Cana to ask Jesus to heal his son. She writes that he walked—and sometimes ran—on his journey. Now we don’t have that information. We don’t know if he ran. Or walked for that matter. Scripture says “he went” (Jn. 4:47).

Mitchell uses walk and run to visually display the emotions that man was undoubtedly feeling as made his journey. Emotions that, again, do not appear in Scripture explicitly but lie implicitly in a story of a Roman officer traveling a day’s journey to beg an alleged Jewish healer to heal his son. It’s an appropriate addition that tells children explicitly what we, as adults—and especially as parents—already feel implicitly.

Taking certain Bible stories and putting them in terms appropriate and understandable for children can be difficult, but it’s absolutely crucial. It’s not an easy task. Whenever I’m considering a Bible storybook anthology, I always turn to certain “controversial” storylines to see how they are handled. Their ability to accurately and appropriately convey the message of the Biblical text tells me a lot about the theological and literary rigor of the series.

Applicable

Does the story have applicational value? Sometimes, children’s Bible stories will simplify the words of a Bible story but not the concept or application. The child goes away knowing what happened, but not why or how it relates to them. It gives them head knowledge but not heart knowledge.

This can most often be in conflict with the value of accuracy, because the Bible isn’t a fable or a morality tale. It is history and history doesn’t always come with a clear-cut applicational lesson. The best Bible story retellings emphasize the applicational value of the story. They put the reader or listener in the perspective of the main character. Or they parallel the ancient lesson with a modern-day point. Or they give us a call to action to emulate (or avoid) whatever principle is paramount.

The downfall of this can be the reduction of a biblical narrative into a fable or any other type of children’s book. Jesus becomes another character alongside Mickey Mouse, Caillou, the Berenstain Bears, or whatever other characters they might encounter. The best Bible storybooks weave their applicational values throughout the narrative as a natural form of storytelling.

It is so very important that our children end up learning the whys and hows behind the what. Telling them a story isn’t enough. We have to show how this ancient narrative remains timeless and can teach us so much in our own lives.

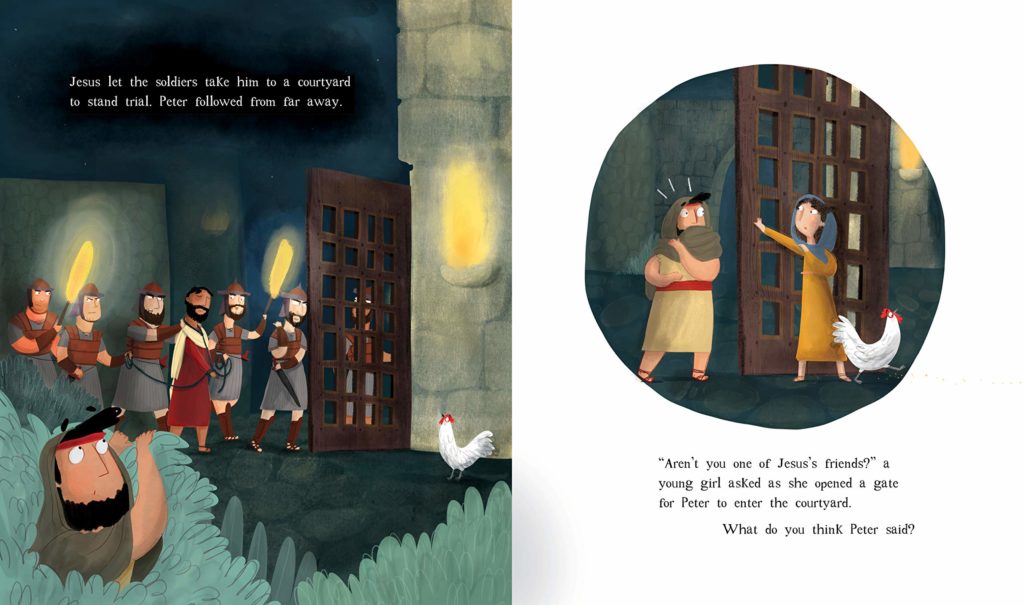

One way of doing this is to try to put the reader or listener in the main character’s shoes. In The Friend Who Forgives, Dan Dewitt tells the story of Peter’s relationship with Jesus. It begins:

A long time ago there was a man named Peter who was best friends with Jesus. He often said the wrong thing. Do you ever talk before you think? That’s what Peter did—again, and again, and again.

We immediately see ourselves as a stand-in for Peter. When the book ends with Jesus forgiving Peter for his denial, the callback to ourselves is easy and clear.

And if you trust in Jesus, he will forgive you, too—again, and again, and again.

When considering a Bible storybook, ensure that it has applicational value. Ensure that the applicational value it has is accurate to the story. Ensure that is accurate to your theology and worldview. This is a book meant to teach your child, so make sure you understand (and agree!) with it. Be ready to talk about it with your child. These storybooks are not the teachable moment; they are the springboard to the teachable moment.

Age Appropriate

Is the content and vocabulary age-appropriate? Not every story in the Bible is meant for toddlers. Or children. Or preteens, actually. (The rabbis actually recommended that nobody under age 30 read Song of Solomon.) It is okay for Bible storybooks to amend their language or avoid content that would not be age-appropriate.

This is why virtually every story of David and Goliath ends with the giant falling and not with David cutting off Goliath’s head. Or with the battle that immediately followed. Or with David’s gathering of 200 Philistine foreskins as a dowry from the next chapter. That’s why VeggieTales went with King George and his ducky instead of dealing head-on with sexual abuse and murder.

More commonly, however, the issue of age-appropriateness comes not from content, but in vocabulary. Are these words that young children are going to understand? If our children are literally not understanding the words on the page, whether spoken or read, the book is failing to communicate any sort of message whatsoever.

I cannot tell you the number of times I’ve picked up a children’s Bible storybook—particularly older ones—to find it littered with King James style English. Not so much with every word, but every theological word. Christianity is often accused of having its own vocabulary. That’s even more true when the audience is children whose vocabularies simply aren’t that complex.

Big theological concepts can be—and must be—reduced into clear and simple language. Oddly enough, I learned this in seminary. I had a professor who always gave an assignment where we had to explain the Gospel in five hundred words or less. The kicker? The grade level of the writing had to score 4th grade or lower.

Look for books that use simple and clear language. Sentences can vary in length, but not be complex. Important words or phrases should be defined or repeated. A great example of this comes in The Garden, the Curtain, and the Cross. The story spans from Eden to eternity, telling the Gospel story. Its theology is rich and deep, but also easily accessible.

The people did a terrible thing. They decided they didn’t want to do what God said. They decided they wanted a world without God in charge. God calls this ‘sin.’

Notice the repeated word use “They decided…they decided.” We’re told what the didn’t want and did want. It’s a whole theology of sin bound up so simply. It takes a theological word that a little one may not understand and immediately makes it understandable.

Later in the book, it defines the temple as “a special building where [God] would live.” It builds tension as it talks about the veil between the Holy Place and the Holy of Holies—though none of this is said in such a formal way.

But then God told people to put A BIG CURTAIN around this wonderful place…It was a big KEEP OUT sign.

Immediately an esoteric concept becomes accessible. And it culminates with:

THE CURTAIN TORE! God had ripped up the KEEP OUT sign. God’s wonderful place is open again! Because Jesus died, we can go in!

Vocabulary and word choice are so incredibly important. Look for a Bible storybook that employs simple words and sentences, word and phrase repetition, and clear definitions of theological terms.

Diversity

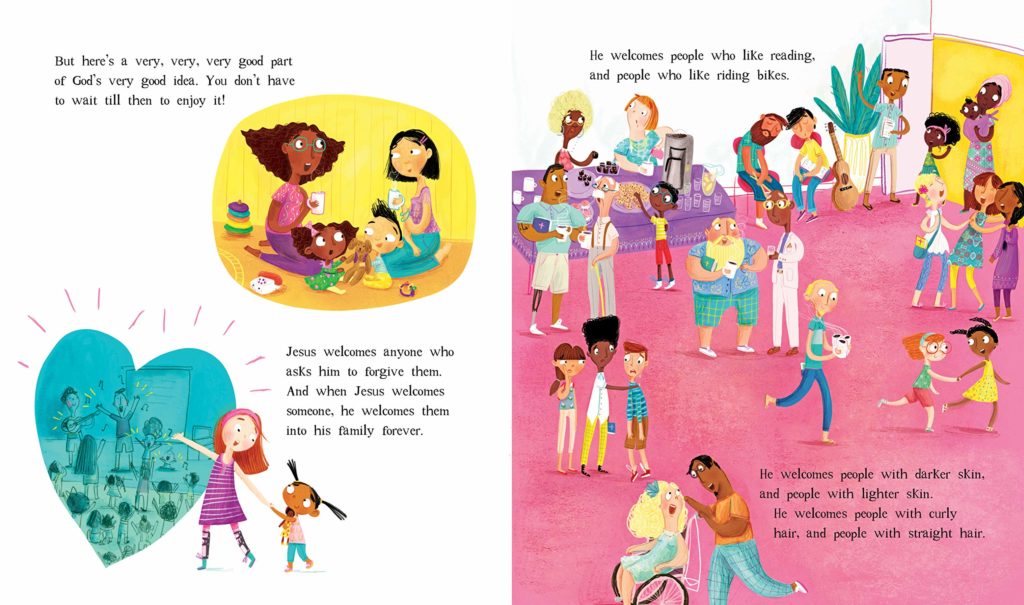

Are the illustrations diverse? In a very real way, this goes back to accuracy. Do the illustrations look like a first-century Middle Easterner would have looked? As the adopted father of a Black son and Middle Eastern daughter, I will very often judge a children’s Bible story by its cover—or at least its Jesus.

Is Jesus white? Probably not going to buy it. Do the illustrations feature a diversity of color that is not just representative of the actual first century Middle East but also of the diversity of the modern world? Then I’m going to pick it up.

Simply put, accuracy matters. And if we are going to demand it in the written story, we deserve in the illustrated story as well. In more ways that once, and in many more spheres than children’s Bible literature, Jesus has been whitewashed almost beyond recognition. And he usually takes the rest of the crew with him. There’s no excuse, in an illustrated book, not to illustrate accurately.

Wes McAdams, the host of Radically Christian, writes of a time that a non-white student in his mid-grade Sunday School class insisted “I can’t be descended from Adam and Eve, because Adam and Eve were white.” Think of what this teaches. Accuracy is important.

But so is representation. I find it okay—in fact, I encourage—a book to show me people in a variety of colors. The Middle East of Jesus’s day would have actually been a reasonably diverse place. Jerusalem is a hub between Europe, Asia, and Africa. People of all ethnic backgrounds appear as followers of Jesus in Scripture.

A diverse cast of characters tells me that an illustrator is thinking of accuracy and of their audience. They are thinking historically and theologically. They are both presenting things as they were and as they should be. So when searching out a children’s Bible storybook, look for diversity. Look for representation. And don’t be afraid if conversations about race, ethnicity, and skin color follow.

Tales That Tell the Truth

Most of the positive practical examples from this article were taken from a series called Tales that Tell the Truth, published by The Good Book Company. Reviewing this series is what served as the impetus for this article. I’ve had these guidelines in my head for a while, but seeing how strongly this series reflected those values encouraged me to write them down to share. You can see each individual review by clicking the series link above.